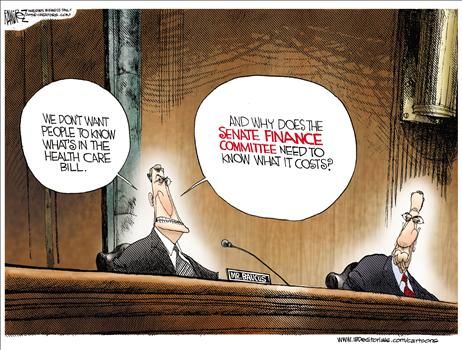

Their actions make you wonder what THEY are afraid of...

" “Come on,” the general surgeon finally said. “We all know these arguments are bullshit. There is overutilization here, pure and simple.” Doctors, he said, were racking up charges with extra tests, services, and procedures.

The surgeon came to McAllen in the mid-nineties, and since then, he said, “the way to practice medicine has changed completely. Before, it was about how to do a good job. Now it is about ‘How much will you benefit?’ ” "

The narrative continues:

"To determine whether overuse of medical care was really the problem in McAllen, I turned to Jonathan Skinner, an economist at Dartmouth’s Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice which has three decades of expertise in examining regional patterns in Medicare payment data.

Sirovich asked doctors how they would treat a seventy-five-year-old woman with typical heartburn symptoms and “adequate health insurance to cover tests and medications.” Physicians in high- and low-cost cities were equally likely to prescribe antacid therapy and to check for H. pylori, an ulcer-causing bacterium—steps strongly recommended by national guidelines. But when it came to measures of less certain value—and higher cost—the differences were considerable. More than seventy per cent of physicians in high-cost cities referred the patient to a gastroenterologist, ordered an upper endoscopy, or both, while half as many in low-cost cities did. Physicians from high-cost cities typically recommended that patients with well-controlled hypertension see them in the office every one to three months, while those from low-cost cities recommended visits twice yearly. In case after uncertain case, more was not necessarily better. But physicians from the most expensive cities did the most expensive things."

The L.A. Times article on which you base your conjecture is itself based on data from the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, whose publications paint an entirely different picture (from yours) of why Medicare costs differ enormously from region to region. As a matter of fact, if you visit the site, you will find several of Dr. Gawande's articles listed there - including this one.

So the answer is pretty clear. Medicare costs differ from region to region - not because of differences in the income or "life styles" of local populations - but rather, the differences in the approach by medical professionals and administrators in different areas towards how and how much health care is to be delivered. Furthermore the choice of McAllen as a case study is particularly significant, since another commonly held view is that doctors prescribe more tests and procedures to avoid malpractice complaints, and Texas is one of the few states in the union which caps non-economic damages in malpractice suits.

I think we're going to get into trouble if we start making broad assumptions about health care reform by using stereotypes. When you proceed on the assumption that income is a central determinant in how much care an individual is going to require in later life, what you are really doing is just laying the blame for high costs on "poor" people - while ignoring the real problem. Any free society is always going to have its poor and rich - and everything in between. There isn't much we can do about that. But we can, in the real world, develop more effective guidelines for doctors to rely on when considering treatment options. This concept, by the way, is precisely why the original reform bill proposed by Democrats mandates the creation of an advisory board to do that.

The agreement enabled Partners to secure higher reimbursements from all insurers and gave Blue Cross a competitive advantage in the market. Since the agreement, Blue Cross has raised its payment rates to Partners by 75%, far more than it pays to other hospitals, helping Partners hospitals earn 30% more than other teaching hospitals - resulting in hundreds of millions in extra payments to Partners each year, as the Globe reports. Blue Cross, for its part, dominates with 60% of the health insurance market and has seen profits soar from $82.7 million in 2002 to more than $200 million each year since. Consumers in Massachusetts have faced ever-rising premiums, with individual insurance premiums raising 9% each year, twice the rate of the late 1990's, before the handshake deal." (my emphasis...BTW: Progressive States is a "liberal" site - however all the facts and numbers here are independently verifiable)

What this all boils down to is the rapid escalation of price without any increase in value. In essence, consumers pay more and more for less and less because, unlike other industries, consumer choice has virtually no impact on health insurance. So, expecting that consumers, armed with government sponsored Individual Health Care Accounts, will rush out into the free market and effect genuine change is ludicrous. My solution is as follows:

First, along the lines of your suggestions, create government owned and controlled Health Maintenance Organizations, comprised of government and government contacted assets which deliver actual health care services and are available as an extended form of Medicare to all citizens for purchase with their HCA's. Second, if it is true, as The National Coalition on Health care says, that Medicare and Medicaid constitute 50% of health care spending in the U.S. - why then allow these programs to use this huge bargaining power go out and contract with individual medical professionals, hospitals, drug companies - even private insurers, and drive hard bargains to create managed care plans - again available only for purchase with HCA's. Third, allow private insurance companies to develop supplemental policies which can be purchased with HCA money only if they meet certain, definite criteria.

What my starting point here consists of is essentially the creation of a huge co-op of private citizens, organized on a scale to take advantage of its immense bargaining power to reduce costs and increase value. This contrasts with the current situation, where private insurers own the bargaining high ground and have no built in incentives to offer a better product.

As we are both aware, this starting point does nothing to address the question of supply and demand. I'll consider that in my next post. What do you think so far?

-Chris